Please see below for a list of my recently published work. Additional publication information can be found on my Google Scholar and Academia.edu pages.

For a complete list, see my CV.

Edited Volume

Florentine Political Writings from Petrarch to Machiavelli

2019. Edited by Mark Jurdjevic, Natasha Piano and John P. McCormick. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

In the fifteenth-century republic of Florence, political power resided in the hands of middle-class merchants, a few wealthy families, and powerful craftsmen's guilds. The intensity of Florentine factionalism and the frequent alterations in its political institutions gave Renaissance thinkers ample opportunities to inquire into the nature of political legitimacy and the relationship between authority and its social context.

This volume provides a selection of texts that describes the language, conceptual vocabulary, and issues at stake in Florentine political culture at key moments in its development during the Renaissance. Rather than presenting Renaissance political thought as a static set of arguments, Florentine Political Writings from Petrarch to Machiavelli instead illustrates the degree to which political thought in the Italian City revolved around a common cluster of topics that were continually modified and revised—and the way those common topics could be made to serve radically divergent political purposes.

Peer-Reviewed Articles

Neo-liberalism, Leadership, and Democracy:

Schumpeter on “Schumpeterian” Theories of Entrepreneurship

2020. Online first at European Journal of Political Theory.

This article reinterprets Schumpeter’s theory of entrepreneurship in a decidedly un-“Schumpeterian” way, and argues that continued emphasis on Schumpeter’s alleged glorification of the entrepreneur constitutes a missed opportunity for democratic critics of capitalism and neoliberalism. I demonstrate that Schumpeter did not exalt the individual entrepreneur as the paradigm for economic and political leadership in capitalist societies, and I show that he offers a surprisingly robust resource for reconceptualizing entrepreneurship. Schumpeter theorized entrepreneurship: (1) as a phenomenon that could not be exemplified by either individual persons or strictly private entities; (2) as a conceptual mechanism for analyzing change in the history of capitalism; and (3) even as evidence that political and economic leadership should not be conflated in modern democratic societies. By contextualizing Schumpeter’s discussions of the entrepreneur, I suggest that a reconsideration of Schumpeter’s actual theory of entrepreneurship would invigorate contemporary debates about the role of leadership in capitalist economies and liberal-democratic polities.

Revisiting Democratic Elitism:

The Italian School of Elitism, American Political Science, and the Problem of Plutocracy

2019. Journal of Politics, vol. 8, no. 2: 524-538.

Contemporary political science has fetishized a product of its own invention: the elite theory of democracy. American political science’s understanding of “democratic elitism” is founded on a fundamental misreading of the Italian School of Elitism and Joseph Schumpeter’s political thought. This essay historicizes the early phases of the interpretive tradition known as democratic elitism, represented by the following authors: (1) Gaetano Mosca, Vilfredo Pareto, Robert Michels, (2) Joseph Schumpeter, and (3) Robert Dahl. I not only track how the Italian School’s concern over the threat of plutocracy was suppressed, and their aspirations for political transparency discounted by American political science, but also trace the shift, over time, in the literary dispositions that undergird what we now call “elite” or “minimal” theories of democracy. I argue that in contrast to the Italian theorists’ and Schumpeter’s pessimism, Dahl infused optimism into his understanding of representative government with pernicious consequences for democratic theory.

Review Essays and Invited Contributions

Just Work for All: The American Dream in the 21st Century. By Joshua Preiss. London: Routledge, 2021. 187p. $44.95 paper.

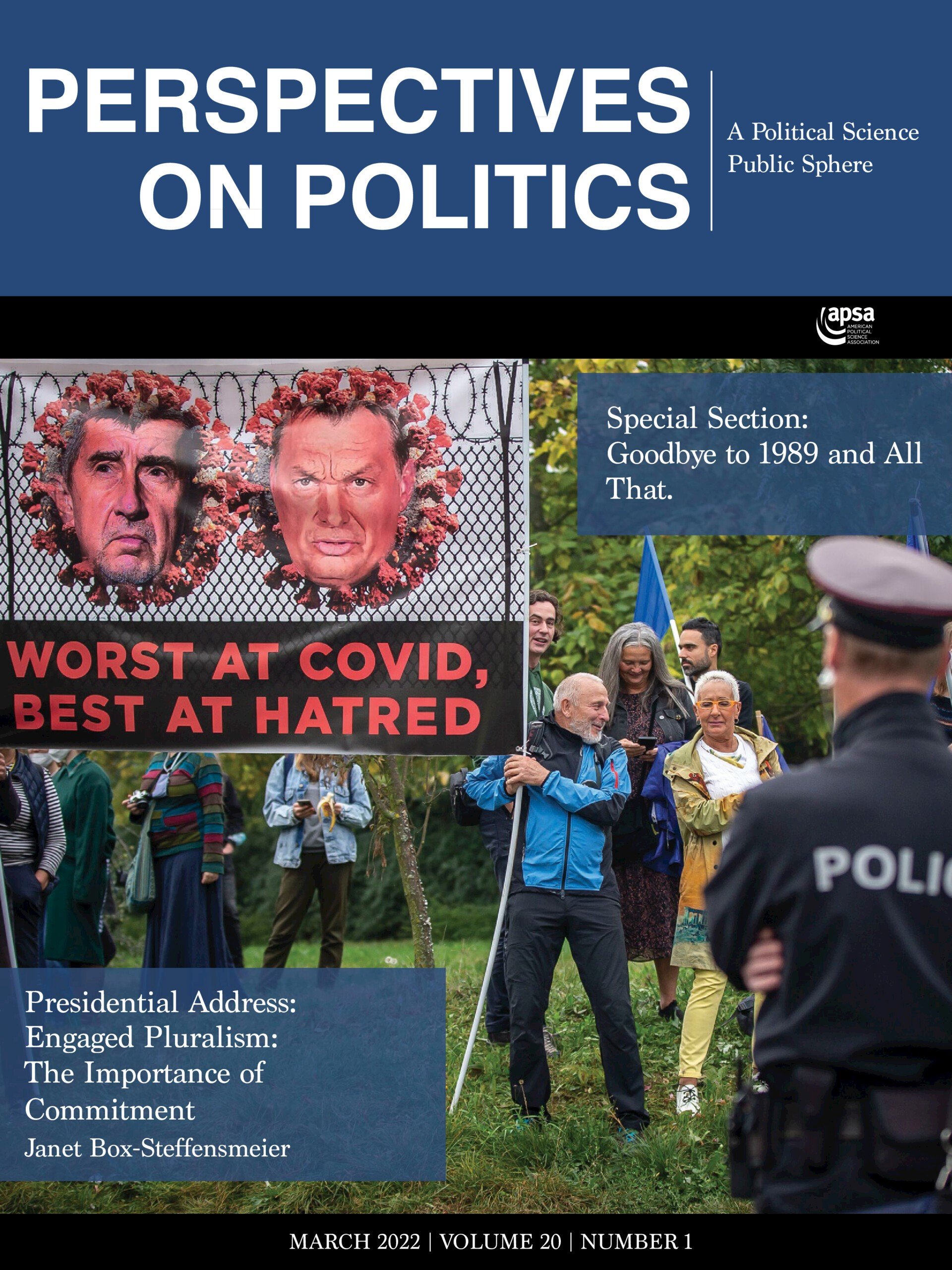

2022. Perspectives on Politics, vol. 20 , no. 1: 307 - 309.

Joshua Preiss’ Just Work: The American Dream in the 21st Century begins and ends with specific policy positions that would be able to generate enough support if they were articulated within the paradigm of just work. Yet these proposals do not capture its main contribution: the American Dream as a theory of justice, a theory that captures shared public intuitions without compromising philosophical rigor.

Schumpeterianism’ Revised:

The Critique of Elites in Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy

2018. Critical Review, vol. 29, no. 4: 505-529.

A close reading of Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy underscores Schumpeter's critique of elite political capacities. Given the neglect of this critique in contemporary scholarship, it might warrant a revision of our understanding of “Schumpeterianism.” To notice the critique of elites, we need to read Part IV in the context of the work as a whole, and with greater sensitivity to the sarcasm, irony, and humor that permeate the book. Such a reading produces a fundamentally altered understanding of Schumpeter's contribution to democratic theory.

Academic Translation

Florentine Political Writings from Petrarch to Machiavelli

2019. Edited by Mark Jurdjevic, Natasha Piano and John P. McCormick. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Translated the following discourses by Francesco Guicciardini from Dialogo e Discourse Del Reggimento di Firenze, ed. Roberto Pamarocchi (Firenze, 1932):

“On the Method of Electing Offices in the Great Council,” pp. 235-239.

“On the Mode of Reordering Popular Government,” pp. 250-279.

“The Government of Florence after the Medici Restoration,” pp. 280-284.

“On the Mode of Securing the State of the House of Medici,” pp. 285-296.

Encyclopedia Contributions

Cambridge Encyclopedia of Political Theory

(forthcoming)

Entries:

“Elite Theory.”

“Joseph Schumpeter.”

Occasional Writing

Why we must stop applying economic standards to political leadership

Promarket, The Blog of The Stigler Center at the Booth School of Business

2021

Schumpeter and Brexit: Same Old Story, Different Ending

Promarket, The Blog of The Stigler Center at the Booth School of Business

2019

What Schumpeter Can Teach Economists About the Great Recession

Promarket, The Blog of The Stigler Center at the Booth School of Business

2018